In this article, I’m going to share a framework I call the Open Gates Model.

Everyone wants quick fixes, and this will be a case for the opposite.

Most quick fixes fail, and I’m going to explain why.

Instead of looking for a single fix, you need to look at six categories that may need fixing.

Let me explain.

How the Open Gates Model Came to Be

In 2011, I became enamored with habits as the solution to every problem in my life.

I believed it was the path to every goal I had for the future.

About a year later, I launched the first “positive reinforcement” habit tracker for the iPhone.

Tiny Habits from BJ Fogg was a big influence, along with other giants of habit formation like Karen Pryor and game designers like Jesse Schell.

That app has helped people start 50 million new habits.

But there was a problem.

Eighty-five percent of the people who use the app to start a habit fail to come anywhere close to permanently adopting that habit.

So, I wondered if there was some strategy that worked better than habit tracking.

That’s how I got into coaching and then later started Better Humans — a publication about self-improvement.

Unfortunately, I found the same low success rate over and over again, and not just in the projects I was involved in.

Some Succeed, Most Don’t

In Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), for instance, the debate over success rates is complicated.

The answer is easy to manipulate in either direction by how you define members.

Subgroups that have been forced to go by the court system have lower success, while people who have been long-time consistent members have higher success.

But the general consensus is that an open-minded person going to AA with a reasonable amount of commitment to following through has a success rate in the 8–12% range.

For weight loss, I led an experiment where I put 15,000 people through a randomized controlled comparison of popular diets.

Each diet performed identically: 12% of people on popular diets lost weight, the control groups, and the other 88% of participants did not lose weight.

(I’ve written about the nuances of measuring success here.)

No matter how enthusiastic people are about some new productivity system or diet or self-improvement advice, the success rate always seems to fall in the range of 5–15%.

Some people succeed. Most don’t.

How can you explain that all advice seems to work only some of the time?

Here’s what I’ve come to: people are asking too much of a single piece of advice.

The information is fine; it’s just being given out either to people who don’t need it or to people who need a whole lot more than just that single piece of advice.

The vast majority of advice is oversold, in other words.

But oversold is crucially different than being wrong.

The Open Gates Model

To help see how advice may be correct, yet insufficient, I’ve been using the Open Gates Model.

It helps people assess themselves and coaches to assess clients.

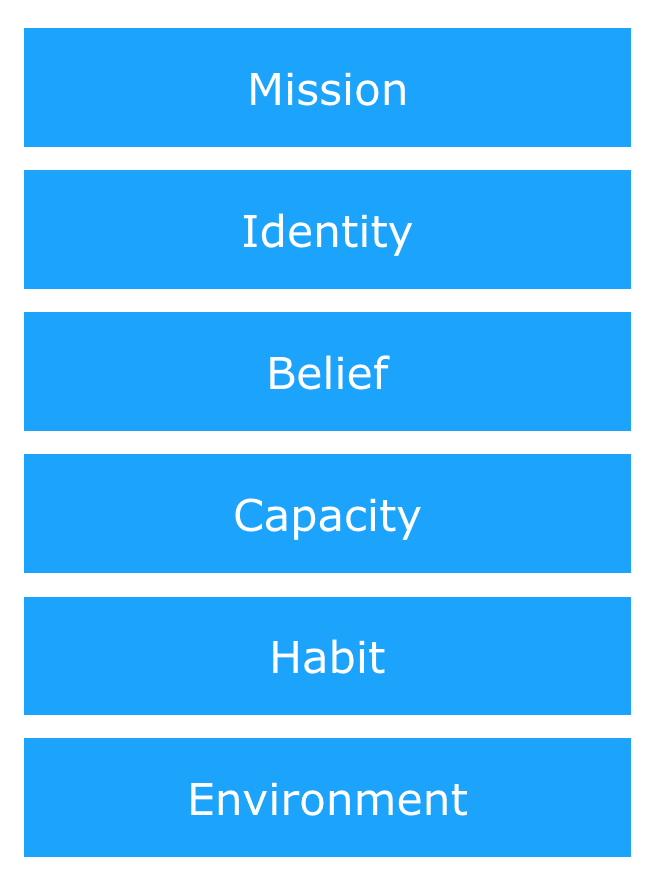

There are six categories: mission, identity, belief, capacity, habit, and environment.

The way to think of those categories is that all six of them need to be addressed.

They are like sequential gates; if even one is closed, then you can’t get through to your goal.

And that’s how I came to refer to this model as the Open Gates Model.

Your job as an ambitious person, or as a coach, is to figure out which gates are closed and then open them.

Sometimes, your habit gate is closed, and the rest of them are open.

This is when our habit tracker, the Tiny Habits method or a book about habits are going to feel life-changing.

But a lot of times, two or more gates are closed.

And that’s why narrow, one-size-fits-all advice feels so frustrating.

Your friend swears to you that Tiny Habits is life-changing, but for you, you also need a second thing.

Sorry, but I’m out to kill the idea of “one simple trick” advice.

You need to steel yourself to try as many as six tricks.

The Origins of the Open Gates Model

The categories that I use are inspired by a famous author in the NLP world, Robert Dilts.

His “logical levels” model is often used to explain different levels that could be addressed by change agents like coaches, therapists, consultants, and parents.

Most often, coaches and therapists work in the categories of purpose, identity, and belief.

A personal trainer, weight loss coach, or athletic coach spends most of their time on capability, behavior, and environment.

The key thing I want to highlight, though, is that for you and your goals, these categories are not hierarchical, i.e., a pyramid.

You need all of them to be functioning.

And it’s possible and common to be blocked by any of these, which is another case against looking at these as a hierarchical pyramid.

That is the major adjustment I made as I moved from reading about Dilts’ model to trying to figure out why my own customers weren’t meeting their goals.

The Open Gates Model Categories

Let’s get clear about these categories.

Environment

You can’t effectively practice basketball without a basketball and a hoop.

Things in the environment category include tools, external triggers like alarms, available time, and supportive family and friends.

Habit

You don’t lose weight by changing one meal on a single day.

A lot of goals require a consistent behavior change over weeks, months, or years.

This category is about building that required consistency.

Capacity

Skill and strategy are usually the key elements of capacity.

For example, to improve at chess, learn strategies for openers.

But you should consider mental or physical issues here as well.

If you are suffering from anxiety, then all your other work is going to suffer as well.

Beliefs

These are things you believe about how the world works or how other people work.

When you are wrong, you’ll get stuck.

The problem is that we all have many beliefs that we haven’t ever articulated.

So, we might not even know when a belief is getting in the way.

Identity

These are the beliefs you have about yourself.

If you believe you are a great improviser, you may find yourself resisting making a plan.

If you are proud to survive on limited sleep, you’ll avoid better sleep habits, no matter how much science says that this will improve your productivity.

Mission

These are the things that are important to you, your life goals, your purpose.

A lot of people quit making progress simply because they find the work required isn’t justified when compared to their other goals in life, i.e., they have better things to do.

An Example of Mission Breakdown

When I started my company, I shared my office space with some people who were deeply into the sport of cup stacking.

Cup stacking is a weird sport that’s basically a test of speed and dexterity.

The challenge is to see how quickly you can stack and then unstack a set of plastic cups.

I tried out the sport and achieved early times on the official test in the thirty-second range.

Later, I learned the optimal strategy, and I got my time down to fourteen seconds.

However, the world record for this not-very-important sport is under five seconds.

In the Open Gates Model categories above, what I did to go from 30 seconds to 14 seconds was to train my capacity and my habit.

A lot of times, capacity is synonymous with skill.

Knowing the right strategy improved my capacity to stack quickly, and then practice created the habit of using that strategy efficiently.

But then I stopped improving.

Even though I was using the same strategy as the elite cup stackers, I was still more than ten seconds slower than them.

What went wrong? Did I need better habits? No.

You might have guessed this already, or at least thought this about yourself.

I stopped improving for the same reason you would stop improving: we both have better ways to spend our time.

The issue is with the Open Gates mission category.

Practicing cup stacking was not my mission in life.

This trivial example is actually the most common reason people fail to achieve a goal.

They realize that success is hard and time-consuming.

Then, they realize that they have more important things to do.

An Example of Tricky Limiting Beliefs

This example comes from meditation.

I’m talking about the simple, breath-based meditation that apps like Calm and Headspace teach.

In these apps, the teacher spends a lot of time addressing your wandering mind, saying things like: “Now your mind may have wandered, this is okay.”

Still, when I surveyed people who had tried to start a meditation habit in our app, I found that the most common reason people gave for failing went like this: “I tried, but my mind kept wandering. I couldn’t get it to stop wandering, and so now I think maybe I’m just not cut out for meditation.”

The teacher and the student are failing to understand each other correctly.

The teacher thinks the wandering mind is normal.

It’s guaranteed. Everyone’s mind wanders.

One of my meditation teachers, Will Kabat-Zinn, told me: “If your mind doesn’t wander, you should go to the hospital.”

Failing students are thinking the opposite; that the goal is to stop the mind from wandering at all.

They believe they are failing.

I liken this to a straight-A student being told that getting a C is “okay” because it’s still a pass, and they’ll still graduate.

When an A-student hears the meditation teacher say it’s okay for your mind to wander, they hear the same: “It’s okay for other people, but not for me.”

Finding the Closed Gates

In the Open Gates Model, the problem of the failed meditators is not solvable by any habit system.

You can’t anchor the meditation habit or stack the meditation habit or make it tinier.

The problem is not the skill side of capacity — the guided meditations tell you precisely what to do when your mind wanders.

Instead, these people are failing at meditation because their identity gate and their belief gate are both closed.

They identify as high achievers. It’s not enough to be okay. They want to be more than that.

Someone who’s not expecting perfection from themselves isn’t going to flip out when their mind wanders.

After all, the meditation teacher said that that would happen and said it was “okay.”

They believe both that the goal of meditation is to calm the mind and that the mind can be perfectly calm.

Neither of which is right.

Together, this combination of identity and belief blocks people from following the directions given by the meditation guide: “When your mind wanders, acknowledge where it wandered to and then bring your focus back to your breath.”

The literal directions are easy to follow, to the point that meditation seems almost impossible to fail at.

And yet, these other gates allow for some very complicated ways that a person can get stuck.

Reframing Beliefs

In situations like these, the coaching skill of reframing can be very helpful.

Beliefs are often hard to change and identity even harder.

When I teach meditation, I reframe the whole cycle of noticing your wandering mind and then bringing your attention back to your breath.

I tell my students, “This is a Mental Pushup. I want you to get stronger at both noticing your thoughts and bringing your attention back to a point of focus. The more your mind wanders, the more pushups you’ll do, the more mental exercise you’ll get.”

With that reframe, wandering minds are suddenly the goal.

That works well with the overachiever’s identity.

Technically, the reframe does change the person’s belief about what to expect about the wandering mind, but it doesn’t change the person’s identity.

Instead, it gives them a set of beliefs that are compatible with their identity.

So this is to say, there are many subtle ways of opening up a person’s gates.

How to Apply the Open Gates Model

So how does this help you, given that you either have a big goal in mind or are a coach helping someone else with their big goal?

The main lesson is that you need to poke at all six categories and evaluate if there is a block there.

Sometimes, you might just need to focus on one category. If that’s true, then you’re lucky.

But more often, you’ll need to devise strategies for all six.

There are basically two times to pull out this model.

The first is before you start on a goal.

A lot of us do this naturally for several of these categories.

If our New Year’s Resolution is to go to the gym, we get a gym membership (environment), buy some new gym clothes (also environment), read up on a training routine (capacity), and tell our friends that this is our Resolution (mission).

But what if you see yourself as someone who hates the gym (identity)?

Most people don’t think to address that and instead hope to grit their way past blockers.

The second time to pull out the Open Gates Model is when you fail, even a small failure.

This model helps you ask questions about why you failed.

Gates to New Possibilities

When I first started working with habit coaches, we had a client who confused us.

He wanted to give up sweets (habit) to lose weight (mission).

But he couldn’t even make it through one day without sweets.

So we kept making the goal tinier for him.

No sweets before 5 pm. No sweets before noon. Just no cookies.

No amount of making the goal smaller seemed to work.

So this client suggested his own tiny habit.

He was going to start by just giving up ice cream.

He talked through replacement habits.

And then he reported in late the next day, “You’re never going to believe this. I failed again. What happened is that we were on vacation in Vermont and my family wanted to tour the Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream factory…”

At the time, we had no tools other than to say, “Maybe you aren’t ready.”

But if you looked at the model and had a chance to talk to this person, you might find all sorts of promising gates to open.

Does he think it’s rude to say no to his family (belief)?

Does he struggle to tell other people what he needs, i.e., to not be anywhere near ice cream (capacity)?

A Final Note on the Open Gates Model

If you are a coach, it’s fruitful to teach this model to your clients and just ask them if they have any ideas.

Usually, you’d say something like, “We’ve been focusing a lot on building the habit, but that doesn’t seem to be working. Could I teach you something called the Open Gates Model and then ask you to think about whether there might be another area that’s blocking you?”

Show your clients the gates, and they might just open them.